Hmong-Laotian American Experience in Burke County

Overview

Burke County is home to a significant population of people who immigrated from Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. While each country represents people groups with unique cultures, a majority of the immigrants here are from Laos of ethnic Hmong and Laotian groups. Laotian is the ethnic majority in Laos and Hmong are an ethnic minority. Both are political refugee groups that started immigrating to the US in the late 1970s. The Hmong, and some Lao, served as the CIA’s frontline soldiers in the “Secret War”, the Lao theater of the Vietnam War.

Hmong trace their origins to ancient China around the Yellow and Yangtze River Deltas, and Laotian are native to Southeast Asia - making up 53% of the population mostly concentrated in the lowlands of Laos.

For a deeper dive into Laos’ history, click HERE.

In the early 1990s, to get off government assistance, many Hmong and Laotian began looking for job opportunities. Unable to apply their rural lifestyle to their new metropolitan homes in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, many started looking to re-settle on the east coast. North Carolina was an attractive option due to a large number of jobs in textile and furniture. Additionally, the beautiful mountains were a peaceful lure to those who missed Laos. Today, there are over 10,000 Hmong in Western North Carolina and about 40 Laotian families in Burke County. A large majority have settled in Morganton, Hickory, and the Charlotte area. Today, Hmong and Laotian work in all industries from manufacturing, healthcare, and the trades. They are also business owners and entrepreneurs.

Hmong-Lao in Burke County | As seen through…Phetoudone Nivanh

Storytelling can bridge boundaries and hearts, connect us to one another, and aid in the understanding of our individual or collective purposes in life. Sharing them can serve as a magic medicine for life, encourage us to challenge ourselves, or give us permission to forgive those who have wronged us. Learning how to connect with others takes time and requires the art of listening and compassion building; as you read my story below, I hope it will spark you to share your own.

—Pat Nivanh

BACKGROUND | From Laos to Burke County, North Carolina

My name is Phetoudone Nivanh. I am Asian American and one of nine children in my family. I was born in Xieng Khouang Province, Laos in 1981 to a Hmong mother, Oneia Vue, and a Laotian father, Thoum Nivanh. My mother was a merchant who sold and traded goods while my father served in the Royal Lao Army as a nurse.

After the Vietnam War, Laos fell to communist forces so my family fled in 1983 to avoid persecution. We found refuge in neighboring Thailand after being smuggled across the Mekong River. We are lucky to be alive because the Communist Pathet Lao Army would patrol the Mekong River day and night to stop or shoot anyone crossing the river to Thailand. We heard horrifying stories about families who were either returned to Laos, killed, raped, tortured, or separated - some were never able to reunited with their families. The Mekong crossing was traumatizing for us because we were a large family of ten and had to split up between two boats - each one crossed at different times and locations. It took my parents a horrendous 7 hours of searching to reunite everyone. To prevent my infant brother, Bounthanh, from crying, my mother gave him sleeping medication. It was not unheard of for families escaping Laos to lull crying children to sleep with medicine or small doses of opium - a crying child could alert troops looking for escapees. Later, he ran a high fever and it affected a certain part of his brain. Today, he is physically healthy but has a mental disability due to the fever. He is the most kind, loving, and giving person that I know. Without even knowing it, Bounthanh made sacrifices for the family and we are forever grateful to him. My family was desperate and we all risked everything to be alive. Once we were in Thailand, we stayed in a refugee camp for two years before my mother’s Hmong relatives in Colorado sponsored us - they had fled Laos a couple years earlier.

In 1986, our family of ten arrived in Colorado where we lived in a tiny two-bedroom apartment. We arrived poor and broke, and owned nothing but the clothes off our backs. We received government assistance such as cash to help pay for rent and food stamps - which was greatly appreciated, but it was still barely enough to get by. In addition, local churches would donate gently used clothes, toys, and houseware to help my family get off our feet. In order to save money, my mother said that she would put away one to twenty dollars a month for several months. Her knowledge as a former merchant helped our family tremendously. We were grateful for our time in Colorado, but we decided to move to California where we had more family and a bigger Asian population to help offset the foreignness of our new home.

In California we were placed on welfare and received government assistance. A requirement for the benefits was that my parents would have to attend school or take classes to gain an employable skill in order to find a job. They eventually acquired their driver’s license, and started a vegetable garden to help feed the family as a supplement to welfare. They also worked as farm laborers picking plums and berries - making fifty dollars a day for 8-hour shifts. Ultimately, it was selling food at the Hmong New Years which eventually gave my parents the opportunity to start saving more money. The work was very hard so my siblings and I - all between the ages of 5 and 15-years old - pitched in to help. We traveled to big cities like Fresno and Sacramento to vend for days at a time. We spent nights sleeping on the floors of relatives’ homes, and woke up between 4am-5am to head out to the location of the Hmong New Year to sell food (which was prepared the night before). We lived in California for 4 years and worked every year vending at multiple locations. My parents were frugal and taught us to be frugal. Eventually, my parents were able to purchase a van to help move us across the country to North Carolina in 1993.

My parents decided to move to North Carolina to get off welfare and pursue job opportunities in manufacturing, and because the mountains in Western NC reminded them of Laos. We relocated to Morganton, Burke County and we have lived here ever since. Both my parents worked in factories making minimum wage while all the children attended public schools and colleges in North Carolina. Both my parents retired from the company they started with. They used welfare and government assistance to help them get on their feet, but they refused to rely on it for the rest of their lives. Because of this one single decision, none of their children are on welfare nor the generation after. There are other contributing factors that shape us as human beings, such as societal structures, economics, and expectations, but they also taught us to think outside the box to make a better life for ourselves. My family is not wealthy but we work hard to earn what we have. So, it is very hard but it can be done. This is my family’s epic journey to Burke County.

Phetoudone Nivanh

Nivanh Family

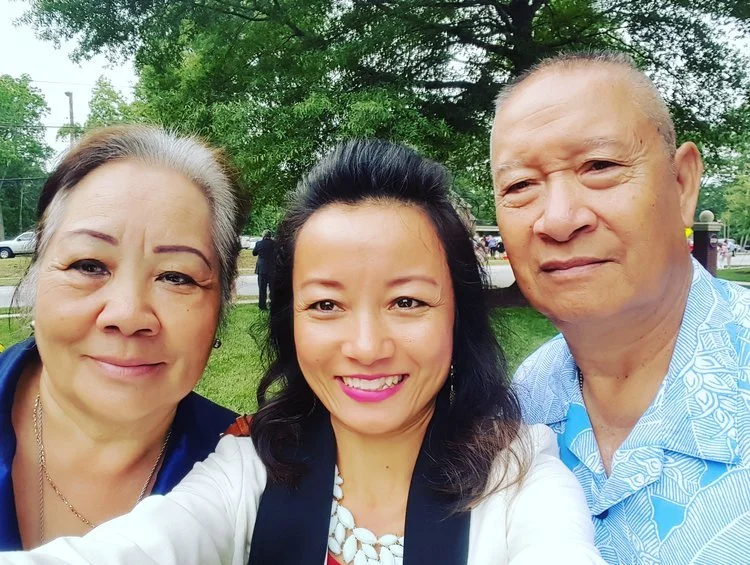

Oneia Vue and Thoum with Phetoudone

Nivanh Family

PERSONAL JOURNEY | What’s in a name?

My name, Phetoudone, means “Diamond in the Sky” in Lao. It’s ethereal and romantic, so you would think I embraced the uniqueness and beauty of it, but it was the opposite. To me, the spelling looks odd, the pronunciation sounds like a dinosaur, and - with ten letters - people might be frightened when attempting to pronounce the darn thing. The name made me feel different and I felt embarrassed by it. I didn’t want people to make fun of me in the present or future, so I developed a brilliant plan to change it in second grade. While learning to spell cat, hat, rat, I noticed the association of the letter P with my first name and decided to add “at” to make it PAT. From second grade and onwards, I insisted everyone call me Pat - and they did. Even to this day, my family and friends will call me Pat. From a young age I felt so much pressure to fit in and I assumed changing my name would help me blend in. I failed to recognize that others lacked knowledge of my culture and did not know how to help people like me not feel alienated. As I grew older I moved further away from my heritage by doing things that were not typically “Asian”. Looking back, I was a frightened young person in a foreign country and found it hard to be Asian in the 1980s.

My acceptance of my real identity as an Asian-American did not happen until quite recently - when I returned to school to pursue a leadership certificate from NC State University. I had to read required literature about Asians in the US and it was a turning point for me - for the first time, I realized I was not alone in my struggles. It confirmed that I was not the only one who felt the need to assimilate and follow the status quo, and expanded on the stereotypes of the “model minority” and how it harms rather than help us. Through this revelation, I forgave myself for being so hard on my younger self, and now I fully embrace my uniqueness and the name that means “diamond in the sky”. My postsecondary education journey taught me to finally accept myself.

Obtaining higher education is also one of my greatest triumphs: I was the first in my family to graduate with a college degree. During my studies, I had no idea of the impact and influence it would have on my siblings, nieces, and nephews. Today, many in my family hold associate degrees, bachelor degrees, and even a doctorate degree. As a result of my education, I have had the privilege to be able to work as a deputy clerk and to be able to treat students to dinner as an appreciation for their help with summer camps. On the other hand, I have faced many instances of racism in my career as well. One example is when a client did not want me to assist with their estate work because I “would not have the knowledge to help” her and she “wanted [my] white colleagues to help”. In other employment, I faced multiple red tapes when I tried to promote cultural diversity. Through the mist of these challenges, a passion was born inside of me as a result of the racism, class structures, economic status, and gender issues I had faced or witnessed. I wanted to expose students to other cultures and ideas and prepare them for college, and I would work hard to make it happen.

I want diversity and inclusion to be meaningful and not something that those in power promote on the surface but not in practice. The barriers I faced have fueled more determination in my soul to never give up. One door may close but I know somewhere another door will open for me and others too. And we can start by embracing and telling our own stories first.

Bounthanh and Phetoudone Nivanh